‘You can’t be held hostage by the brook’

February 22, 2024 at 12:18 a.m.

For a few minutes here and there, the aura would become happily boisterous as neighbors sat around Peter Corcoran’s dining room table at 14 Brook Ln. Though ultimately, they had gathered on the evening of Tuesday, Feb. 20, with intent to voice the desperation of their frustrations, jokes at each other’s expense were cracked all night, along with a few beers.

“It’s a real neighborhood here, it really is,” said Paul Williams, who lives at 11 Brook Ln. And that’s just one of the factors adding strain to their situation—when the most inhospitable resident on the street is Mother Nature.

Brook Lane residents, along with a few other pockets around Rye Brook, are grappling with the decision to stay or go.

For some, such as Janine Logue, the choice isn’t so hard. She’s lived in her house at 8 Brook Ln. for the last 30 years, but in her case, it stopped being “home” on Sept. 1, 2021—the day Tropical Storm Ida hit, instantly traumatizing the community as a life-changing moment.

“Some people are emotionally attached, and I understand that; we are not,” Logue said during a phone call last week. “It’s just a shelter, not a home, nothing I’m attached to. Because the things you get attached to are gone—the photos, the memories.”

Those pieces of sentimental value that make a home were swept away or ruined in the flood.

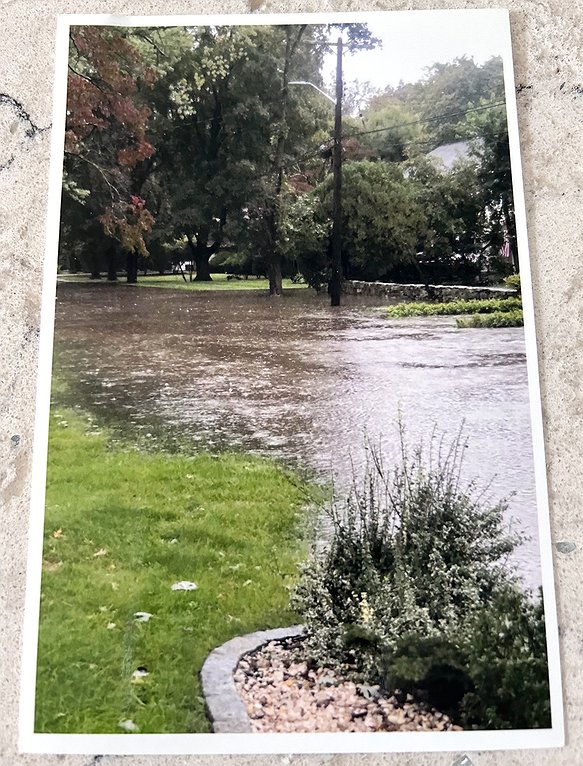

Brook Lane was ravaged by Tropical Storm Ida as a 5-foot river engulfed the street and soaked many homes. While historically it was the even-numbered houses directly adjacent to the Blind Brook that have been vulnerable to flooding during drastic weather events, this storm proved no home is completely safe as even structures across the street saw severe damage.

Ida was the storm that brought about the Village of Rye Brook’s interest and participation in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS) Recovery Buyout Program, particularly as it’s well known that with changing climate patterns such events will only get more frequent. The voluntary initiative gives eligible homeowners a way out of their flooding-prone properties by using federal funding to purchase their land.

Among the qualifying property owners on Rock Ridge Drive, the Wyman Street area and mostly Brook Lane, 22 residences signed on to move forward in Fall 2023, according to Village Administrator Christopher Bradbury. At the end of the day, Rye Brook will attain possession of all properties that choose to accept the buyout, and the Village will be mandated to take down the structures and maintain it as undeveloped land.

Since last Fall, the Village hired an appraiser to assess the properties opting to move forward with the program. Tasked with determining an evaluation based on the day before Tropical Storm Ida struck, the appraiser spent several months putting together what would ultimately be the homeowners’ offers, which have now been distributed to everyone who signified potential interest. It’s currently the final hour, as residents are figuring out whether they want to take part in the acquisition.

Additionally, an extra incentive recently popped up with new access to a supplementary program provided by The Nature Conservancy, Bradbury said.

“That’s a brand-new pilot program that’s meant to encourage improving floodplains,” he said of the environmental organization’s initiative with a stated mission to return land to nature to protect communities and future generations from flooding. “It’s encouraging property owners to accept the buyout program by providing up to 3 percent of the assessed value as an additional payment.”

Communities such as Brook Lane undeniably faced collective trauma from Tropical Storm Ida. Still, not all residents are convinced that a federal buyout is the right way to go.

“It’s like there are 50 percent of the people who say they want to get out and will take the offer, and then there’s the other half of the community who wants to stay, especially if they’ll just fix the brook,” said Williams. “For us, we’re still on the fence.”

“My wife was born and raised in that house, but we have a daughter in Florida, a daughter in Costa Rica, so we do have incentive to leave in some ways,” he continued. “But then, the fact is, she’s been here for all that time, and just the logistics of moving and the sale, it’s a lot. And then the absolute pathetic treatment we’ve gotten from the Village.”

Upset and skeptical, some are wary of the buyout

“We’re the forgotten part of Rye Brook,” Corcoran said, exhausted by defeat.

“The poor relatives of Rye Brook,” Williams added. “Relatively speaking, we are the poor neighborhood, and you really feel like we’re being treated like that.”

Their frustrations are rooted in the growing belief that their Village, and their elected representation, doesn’t care about them—they feel that’s seen in the options offered to them and their situation’s perceived priority as an issue.

“I didn’t put my papers in, I’m not doing it. I had everything filled out, but never handed them in,” said Daniella DeLuca of 15 Brook Ln., agreeing with their sentiments. “It just didn’t feel right. We had a whole family discussion, and something about this just wasn’t feeling right.”

Tropical Storm Ida was disturbing. Patricia Crowley, a resident of 17 Brook Ln., described it as “absolutely frightening, and shocking, because we had never seen it like that before.”

Living in the house she grew up in with her octogenarian parents, Crowley’s home didn’t flood that evening, though they watched the water come up to the door. But she recognizes that she was one of the lucky ones—it was a dire situation she called “life and death,” referring to the Rye Brook couple, Ken and Frances Bailie, who died that night on Lincoln Avenue. “That could have been any of us,” she said. And given the severity, she’s suspicious to see few improvements of tangibility made to help their situation, which she feels may be a method of pushing residents toward the NRCS program.

Crowley’s household also chose not to consider the buyout.

“I was in the early meetings when they brought this up, and it didn’t feel like it was above board to me. They didn’t have any answers to questions,” she justified, and later continued: “Moving is such a huge expense. We cannot get an equivalent home in this community for what people are being offered. We’re losing with this deal, and it’s evident.”

“This is the easiest solution for them, but not for us,” she added. “There are other solutions out there, but they’re being hidden from us, which is very strange. It makes you wonder, why are they so interested in getting the residents of Brook Lane to move out?”

She questioned who benefits from the neighborhood disappearing. The group generally felt their exodus would be orchestrated for the benefit of Rye City, which has not pursued the NRCS program and has neighborhoods that flood downstream from them, and corporate entities that contribute to the problem but are hesitant to sacrifice their land.

Several in the Brook Lane neighborhood think the governmental response to their trauma should have been handled differently—the goal should not have been about getting them out but solving the problem through long-needed infrastructure investment.

“We’re not looking for money, we want them to fix the brook,” DeLuca said. “Help the residents who live here.”

“We just want to return to the status quo,” Crowley added. “We don’t want anything more than that. We want to return to a safe place.”

Flooding issues are not new to the area; Corcoran had been a “fix the brook” advocate for years prior to Tropical Storm Ida. The retaining wall on the medical facility’s property in Harrsion across the stream has been creating a bottleneck in the river for years. And time and time again, studies have shown that water basin or berm projects upstream, on the SUNY Purchase campus, would have beneficial effects for them. Whether it be widening the brook or adding more drainage pipes—the neighbors have collectively put together a laundry list of suggestions that don’t involve their departure.

Crowley frequently pointed to the November 2022 “Flood Mitigation & Resilience Report” from the State Department of Environmental Conservation and Office of General Services, a 200-page study that laid out flooding issues on the Blind Brook. Part of it shows potentially effective mitigation measures on their section of the stream, with one option creating a flood bench in their neighborhood and another doing the same in the Harrison parking lot across the river.

“If we were to do this program, we’d have to leave this area. So where would we go? The other alternative is you become an apartment dweller, a renter. Your lifestyle is compromised either way; there’s no equivalent. And what’s frustrating is this can be helped, they can help it,” Crowley said. “For us, chop up the damn parking lot. It’s not like it’s somebody’s house, it’s a parking lot.”

“To sum it up at the highest level, their only interest is getting us out of here,” Williams said. “They’re not interested in listening to alternative solutions, regardless of how rational they are…We think they’re not in the least bit interested in resolving this in the residents’ favor. Whether it’s giving money to fix the brook or giving money for our house at a reasonable price so we can buy something comparable.”

The complication is the “they” the residents are referring to—most of the infrastructure improvements that may help their situation involve cross-municipal cooperation, which has proven to be a task easier said than done.

Village Administrator Bradbury reminded of that reality, noting the Village has no control over the properties in Harrison and the SUNY Purchase berm project proposal was rejected by the college. “This is a regional problem,” he said. “The Brook is on the Rye Brook border, and most of it’s on private property where the property owners maintain it, except for where it crosses public ways.”

The NRCS program, he continued, has always been stressed as voluntary. “No one should be feeling pressured to leave, we’re just trying to create options for people to consider,” he said. “However, if someone chooses not to participate, we’re not turning our back on anyone.”

The Village continues to invest in studies and engineering consultants to try and address flooding issues, he said. They’re also in the process of setting up a warning system that will alert Brook Lane residents when water is rising to concerning levels, among other projects.

Ultimately, the Brook Lane residents who are upset feel it’s the Village of Rye Brook’s responsibility to protect them—legally, as advocates and through infrastructure. They’re frustrated because they just don’t see that happening.

But while some are inherently wary and irate over the situation, others are happy to have the options coming to fruition.

A good option for many

There is popularity in the program being seen.

At this point, all homeowners who opted to begin the NCRS process have received their offers, and after receiving it, they have 45 days to decide how to move forward. The due dates, according to Bradbury, range from Feb. 24 to Mar. 16.

As of Tuesday, Feb. 20, he reported that eight of the 22 eligible property owners had already accepted their offers—four on Brook Lane, three from Wyman Street and one Rock Ridge Drive household.

Logue thinks it’s likely she was the first one to turn in her acceptance.

“We’re very excited; I think we’re really at the tail end of this,” said Logue, who already has a new home lined up in Connecticut. “I feel good about our offer. But even if it wasn’t what we thought it would be or could be, I don’t think it would have stopped us. You have to be able to live your life, you can’t be held hostage by the brook, fearing whatever consequences there are living by it.”

Logue has been eager about the prospect of the buyout since the Village was approved for the program. Concerned that her home had become unsellable, she felt it was her only way out. And frankly, she’s sick of the lifestyle her home has inflicted on her—the fear that overcomes her every time it rains.

Last Fall was a wet one, with several storms sweeping through the area, including one on Sept. 29 that called for an evacuation order in the Brook Lane area.

“I don’t think people understand, when you evacuate, you’re immediately homeless. There’s no saying if or when you’ll be allowed back in. That day we drove around; we sat in front of my mother’s house. When you can’t see what’s going on, what’s actually happening to your home, you feel even more upset,” Logue said. “You exist there, you’re not living there. Every time it rains, you’re looking up the numbers, staring out the window…how many times do we have to take out the flashlight in the middle of the night to look at the brook? That’s how we live.”

Bradbury said the Village is practicing flexibility in the process moving forward, for those who wish to take the buyout. “People have different situations,” he said. “Some have already purchased other homes, others are just starting to look now. Some want it done as soon as possible, some have children and want to work out being settled before next school year.”

Staggering the closings works for the Village anyway, he said, because they don’t have the capacity to process them all at once. The goal is to get everything finalized by the end of the year.

Taking their own route through the market

Corcoran’s home currently has a “for sale” sign out front.

“I have nowhere to go, but I can’t live like this every time it rains,” he said. “I love my house. My heart and soul went into this house. I don’t want to go, but I can’t live like this. I figured I should get another place and start over.”

While he pursued his options, receiving an offer from the NRCS program, on Feb. 20 he reported that he plans to officially withdraw from the program soon. Frankly, to him, it seems he’ll find a more lucrative opportunity if he takes things into his own hands.

And he’s not alone in his thought process.

The cohort of Brook Lane neighbors are skeptical about how the home evaluation process went down. Though Bradbury said the appraisers used specific NRCS guidelines while conducting the work, some residents feel the outcome was “odd and arbitrary.”

Five houses of different sizes and features on the block, they say, were offered the same compensation—$625,000.

“I feel like we were duped by this,” Corcoran said. “There’s no way we could all be exactly the same.”

“They said they’d give you the value your house was valued at the day before the flood. That’s baloney,” Williams added. “We know at least five houses that were offered $625,000, which is about $100,000 below the current market value. The day after the flood, we had the Zillow done, and our house was $677,000. It’s not a million-dollar difference, but it’s substantial. And it just undercuts any credibility they might have. In so many ways, that also typifies how they’re treating us.”

“We’re on the fence, but it’s very difficult for us to consider really taking the $625,000,” Williams said. “We are leaning heavily toward selling it, based on what’s been happening in the neighborhood.”

The residents are dissuaded from the buyout because since Tropical Storm Ida struck, houses on Brook Lane have been selling—and they’re going for rates higher than what many received as offers through the NRCS program.

The property at 20 Brook Ln., for example, was listed for $659,000 and sold last October for $675,000, according to Zillow data. And in Westchester, it must be disclosed if a home on the market has a history of flooding.

“There have been three flooded houses that have been bought, that people are living in, although there is a flood threat,” Crowley said. “It just shows you how in need people are of housing in this area, in this price range.”

Of course, when property owners take their houses to market as opposed to proceeding with the buyout, the flooding issues associated with the land will continue to threaten the neighborhood.

Notably, with that in mind, Bradbury encourages residents to think through all their options.

“They have the right to sell their houses, but we hope the values they received through the program are reasonable,” he said. “If they’re looking to move because of flooding, hopefully the NRCS program will be a serious consideration because that will eliminate the future homeowner (issues).”

Comments:

You must login to comment.