‘Nothing is more important than a well-informed citizen’

March 21, 2024 at 2:08 a.m.

Laurel Lowenthal cares about giving back.

“It might be weird,” she laughed, but she genuinely enjoys fulfilling Blind Brook High School’s community service graduation requirement.

So, when she met Kelley Gordon-Minott stationed at a table in her school’s cafeteria last fall, it wasn’t just the free Jolly Ranchers being offered that enticed her.

Gordon-Minott was there on a mission—to recruit. And Lowenthal was listening.

Gordon-Minott is the instructor of a new free civics course that focuses on awareness and action through a local lens. The collaborative program was fathomed and launched by the Rye, Rye Brook and Port Chester League of Women Voters—run by co-presidents Anthony Napoli and Patricia Rinello—who recruited the efforts of the local organization One World for help.

One World—an education organization geared toward global connectivity that started locally, founded by Port Chester Trustee Joe Carvin long before he was elected to the board—facilitates the civics course. Retired Port Chester teacher Jack Zaccara designed it, and Gordon-Minott brought in some tweaks, Carvin said.

Starting in October 2023 and slated to continue through the end of April, the program has engaged 17 students from four school districts—Port Chester, Blind Brook, Rye Neck and Rye City—in bimonthly sessions that casually yet enthusiastically guide them toward making tangible improvements in their communities.

“I wasn’t sure what this was when I signed up for it, but my understanding was I would learn more about local municipalities and how to be a good citizen and make a difference in my community,” said Lowenthal, a senior. “I was really excited to explore what that could look like.”

She joined with her brother Noah, a Blind Brook sophomore, who described the course as a “step up,” enhancing the civics-oriented education he’s received in the classroom. And that, the organizers described, was the point.

A case for civics enhancement

How many adults, let alone minors, know who the U.S. Secretary of Defense is? Or the difference between the constitutional tenets of the separation of powers and division of powers?

Sadly, to Napoli, the answer is grim.

“Nothing is more important than a well-informed citizen,” said Patricia Rinello, and that’s the crux behind the League of Women Voters’ mission. “We realized, if we’re going to make a difference and encourage participation in civic engagement, we have to reach out to the young people—to inspire them to want to take part in civic leadership, public service, government. And this way, we can help create better citizens.

“We felt that there’s no reason why the League can’t reach out to students to create some kind of initiatives that encourage good citizenship,” she continued. “And that comes from the fact that we were both teachers for many years.”

While both Rinello and Napoli define themselves as educators, first and foremost, the nature of their commitment to community and their careers is ultimately about civic engagement—Rinello as a former Port Chester Board of Education member, and Napoli as the once superintendent of schools.

While some of the information in the course is covered in high school curricula, it tends to be sporadic.

“In reading many research articles, there’s an incredible lack of knowledge about civics and citizenship and their role as a citizen, especially among young people, and that’s a concern to us,” Napoli said. “With Regents mandates, there’s a great deal of pressure for teachers to cover material. But what about absorbing material or coming to truly understand material?”

The course, by design, intends to foster that understanding of civics through a local lens by focusing on real-world applications, discussions, projects and thought experiments—to enhance the education that happens in high school in a way classrooms don’t have the time or resources to pursue.

Gordon-Minott described the League of Women Voters leaders’ fears as valid. Students in the course have expressed a lack of consistency and applied studies.

“They’re learning amendments, they’re studying cases, but it’s not applied. It’s not really connecting to their world where they see the patterns or pull from the past and compare to what’s happening now and really understand how it works,” she said. “They’re learning the stuff, but don’t necessarily use it or have the opportunity to apply the information to see how it’s used in actual modern society. While they study the material, they’re not engaging in what community means.”

There’s also limited awareness about the foundations of their own community, she said. Fostering a non-judgmental environment during the sessions, she’ll have open discussions with the cohort about local government.

“They really don’t know much,” she said. “We started the class off asking them questions about their community. Do they know who the mayor is? Do they know what municipality they belong to? Is it a town or village? Most of them had no clue. So, without shame, and not for a grade—it’s OK to not know, it’s OK to use your phone to look it up—we talk about why it’s important to know who these people are, what they do and how they get things done.”

The New York State Education Department has also taken note of deficiencies in civics education. Newly proposed graduation requirements, which likely won’t take effect for several years, urge a heavier emphasis on it in the classroom.

In a serendipitous way, which Carvin laughed about loving to take credit for, the course started coming to fruition around the same time New York State sanctioned the Seal of Civic Readiness availability for high school diplomas. Ideally, the organizers plan to continue collaborating with schools to align the seal’s requirements with theirs.

“We can make it easy for them,” Carvin said. “Why not join us and get the seal? We’ll give you a leg up, you won’t be left out in the cold.”

Alignment of the programs, the organizers hope, will incentivize growth in the course in future years, as they anticipate it will continue. Even without the seal’s enticement, “I’m confident it will continue,” Napoli said. “I think the students will go back to their schools and speak about the benefits of the program. The fact that you have students continuing to come back is a rating. If they found it totally boring or irrelevant, they’d stop coming.”

“Students, to a degree, are becoming more politically involved,” he continued. “It’s evident by the clubs that are now existing at the high schools. Hopefully, this will expand.”

The Lowenthal siblings have certainly stayed involved, and they’re not the only ones. Commitment to community, and furthering their own education, have proven to be reasons to stay.

A course tailored toward teens

The civics course, in essence, is designed around looking at engagement and good citizenship while hovering around the New York State Education Department’s four pillars of civic readiness: knowledge, skills and action, mindsets and experience.

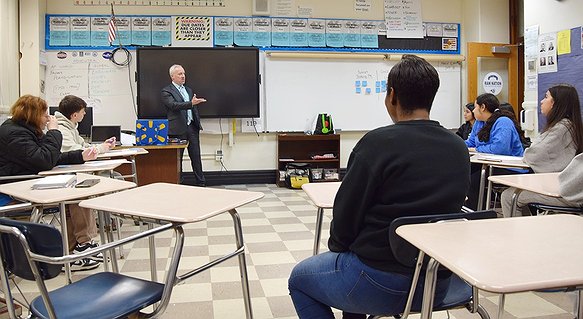

Every session features activities, debates, discussions and guest speakers from the community who are asked to talk on their journey, profession and what citizenship means to them. During a visit on Mar. 5, the class heard from Rye Neck Superintendent Eric Lutinski, who described the importance of cooperation in his role, the value of perspective and the power of leading by example.

“Social studies, which covers these things, is the most important subject. It’s the only one required for all four years of high school,” he said. “In second grade, the lessons are all about community. And that’s pressing, because if you look at the news nowadays, it’s all about people who didn’t get the message.”

In prior sessions, the class met with Port Chester-Rye Brook-Rye Town Chamber of Commerce Director Sylvia Dundon and Port Chester Trustee Joan Grangenois-Thomas, among others.

Rinello and Napoli spoke with them early on about the value of compromise, negotiation and the challenge of developing trust in leadership roles. “I stressed how in recent years, compromise has become a dirty word,” Rinello said. “But being a member on a board, a group where each has an independent point of view, how do you get a group like that to arrive at consensus? If anything, compromise is a sign of strength.”

The diversity of speakers is what holds Noah Lowenthal’s attention.

“I joined the class to expand my knowledge on government and global issues,” he said. “The guests have a lot of experience to share that’s interesting.”

Guest speakers have driven the cohort’s discussions, Gordon-Minott said, and the ways they comprehend what it means to be good citizens and build community. But what’s also crucial about the course, she emphasized, is students are learning about the fundamentals of society building through diversity and comparison.

The participants represent a collection of four different school districts, and meetings rotate among the municipalities and schools every time.

“It’s getting them a little out of their shell. We have students who participated because they wanted to meet other students,” she said. “They want to engage with people from different cultures and see the ways other communities are different and the same. They’re learning from each other about what works in their communities and what doesn’t.”

And that collective energy leads to the course’s culminating highlight: the capstone project.

The ultimate goal of the program is to guide students through demonstrated leadership in civic engagement through a project. Pupils in the inaugural cohort have divided themselves into two groups. One is focusing on connecting their communities, which they’ve discovered are so close yet different, while the other is looking into helping their peers with mental health struggles.

“The connecting communities group, they’re all realizing they’re living in silos. No one really interacts with each other,” Gordon-Minott said. “Their goal is to promote diversity, promote culture and build relationships. So how do they start to do that with their peers and this group? How do they get others in their schools to care?”

By the end of the course, they intend to have plans to host an event for high schoolers across the area—to bring them together to celebrate culture and learn from each other. “But they have to design it,” the teacher said. “What’s really important is they’re seeing all the layers and levels that go into making change.”

The Lowenthal siblings are in the mental health group, which was developed because it’s an issue becoming all the more important to teenagers.

“We made a survey that we’re going to distribute to our peers soon, it has a lot of questions about mental health and what students currently do and what they’d like to see changes in, whether that’s themselves or the schools’ community,” Noah said. “After we have that information gathered, we’re going to introduce something. We’re thinking of having mental health workshops or maybe do a yoga night.”

“Seeing the feedback on the survey, it’ll tell us what people want to see,” Laurel added. “If it’s more like, ‘I want to be aware of more resources in school,’ there’s steps we can take at a more local level. Like putting up posters in school, even if that helps one person, we’d love to see that.”

Comments:

You must login to comment.