Afterschool enrollment skyrockets when affordable program launches

October 17, 2024 at 12:30 a.m.

Since the first day of school on Sept. 3, the elementary buildings across the Port Chester School District have been bustling in the hours after the final bell rings.

Education and enrichment are no longer confined to the hours of a typical school day, a trend that speaks to a national philosophy in the field. For several years now, afterschool programming has been considered a crux of the childhood experience, giving students heightened opportunities and parents more flexibility for work.

“Wow,” said Fallen Jean-Baptiste, taking a moment to reflect about the impact afterschool has had in Port Chester. “In a good way, I get emotional just thinking about it. One thing that’s been consistent with Port Chester is there’s always been a need for childcare. We survey parents and the big feedback is: ‘I appreciate my children having a safe place where I can be at work and not worry.’ And that really hits home; I think about it a lot.”

“I think it’s been very impactful,” she continued. “Families have demonstrated a need, and for our kids, especially the kids who come back year after year, it’s part of their DNA.”

Jean-Baptiste is the director of school age programs at the Carver Center, the community-oriented nonprofit that has a long history of partnering with the school district to facilitate afterschool activities. Her “deeply involved” role over the last two years has been overseeing the program at all four elementary schools—before that, she worked as a director at specific building sites.

The need for afterschool options at Port Chester Schools became apparent last year when the program shifted to an opportunity of financial privilege.

But now, following vocal community feedback, the playing field has leveled. And as a byproduct of the efforts to make the program more accessible, it’s also become more academically driven than previous iterations could offer.

After the community had relished two years of free afterschool programming thanks to COVID-19 relief grants, there was a sense of blindsided sticker shock in the 2023-24 school year when funding ran dry. The situation, costing families $300 per child a month, led to a drastic drop in participation—only 30-50 students in each building enrolled, whereas the free program saw at least 120 pupils in attendance and over 250 in the most populated building: John F. Kennedy School.

A collaborative effort to secure numerous forms of funding, however, wrote a different story for the 2024-25 school year. Over the summer, the district announced the new program would only cost families a $100 supply fee for the entire year.

“It’s refreshing to have a partner in the school district understanding the community and what our families need,” said Carver Center Chief Program Officer Daniel Bonnet. “They’re looking at the community schools model beyond the classroom as something to hone in on.”

Per the agreement with the Carver Center, the afterschool program was designed to enroll up to 187 students from John F. Kennedy Elementary School, 135 from King Street School, 131 at Park Avenue School and 132 at Edison School. And in general, Bonnet said, they’re at capacity and have waitlists.

A participation cutoff had to be implemented due to restrictions set by the Westchester County Office of Family and Children’s Services, the institution that accredited the Carver Center to run the program and awarded it the substantial LEAPS (Learning and Enrichment After-school Program Supports) grant that allowed the program to affordably function.

After establishing capacity, slots were divided evenly by grade to ensure fairness. That’s why some grades at specific schools may see a waitlist while others could have a few seats open.

“The maximum capacity numbers for the program are different than our schools’ maximum capacity,” said Port Chester Deputy Superintendent Dr. Colleen Carroll. “They’re really based on a childcare model, like staff to student ratio, number of students in a space.”

Like a jigsaw puzzle, multiple funding sources had to align to meet the community demand of making the program accessible. The LEAPS grant, a 5-year commitment, provides $900,000. A RECOVS learning loss grant Port Chester Schools earned from the state will bestow $1.2 million for district wide programs over the next two years.

“That’s to service up to 1,000 students in academic programs,” Carroll said. “It could have included other things, but our main focus was to maximize the use toward afterschool.”

“We have to serve 1,000 students at $1,200 a student,” she continued. “So, when we capped out of that for afterschool, we also planned to use it to run a small Saturday program at the Carver Center. And then high school and middle school tutoring for a couple hundred students there.”

The district is also using $350,000 of Title 1 funding, which must be applied for annually, and then $100,000 was earmarked through the general 2024-25 budget—“icing on the cake,” Carroll said, to keep the cost down.

The different money funds also have different stipulations, adding to the robustness of crafting the program.

While the LEAPS grant is geared toward childcare—ensuring the program is provided five days a week for two and a half hours a day—the RECOVS grant and Title 1 funding mandate there is an educational nature to the schedule.

“We provide programming for our kids that’s all-encompassing,” Jean-Baptiste said. “From academic support, all the way to their needs outside for recess or using the gym. The continuation of learning with teachers, that speaks to how things have changed this year.”

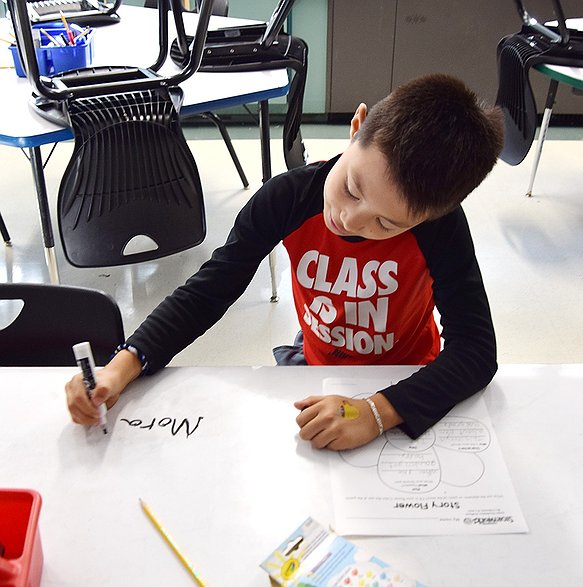

The Title 1 and RECOVS grants have the specific intent of bringing students to grade-level academic proficiency, Carroll explained. And because the Port Chester School District has been keen over the last few years on prioritizing data collection, they and the Carver Center have been able to create a program that’s individually tailored to students to work toward that goal.

“To close the gap, if there is a gap, teachers are provided with past assessments that we have,” Carroll said. Whether it be Star Renaissance, American Reading Company or Imagine Learning data, “teachers can see where the students are at and determine what their needs are.”

“For some students, it may be a review that they need to move forward. For other students, it might be a different way of receiving the information,” she continued. “We’re looking to not repeat the same thing they got all day, but it’s the concepts that may be similar that they may have been taught but not fully digested or internalized. So, the teacher may be using a different resource or material, or potentially even a different curriculum to hit the grade level standard and ensure students get it but maybe just needed to hear it in a new way.”

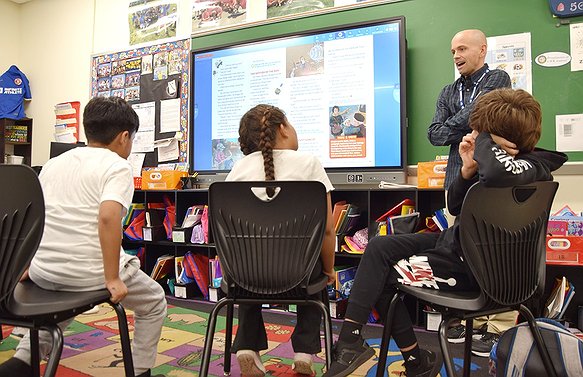

Every day, students enrolled in afterschool spend the first 30 minutes socializing over a “snupper” meal before heading to their designated classroom for lessons and enrichment where there is a strict 10-to-1 student to adult ratio.

Mostly in the first hour, though Bonnet said it can extend throughout the entire afternoon depending on the schedule, students engage in the academic portion of the program.

The Carver Center hired certified teachers, largely from the Port Chester School District, to rotate pupils through small group educational settings. Based on their shared academic needs, a handful of students will be pulled from the classroom together to engage with the teacher to develop a specific skill. When they’re done, the teacher will return them to the classroom where peers are working on homework, educational exercises or reading and pull another small group.

“Our teachers are already trained in our materials, so even if the student doesn’t have that teacher currently, they may have had them in the past or know them just from being in the school,” Carroll said. “Moreover, they know our materials and curriculum and resources, so it’s convenient that they’re already here.”

Of course, as Jean-Baptiste emphasized, the program isn’t solely academic—enrichment elements that have always been popular in the program continue to flourish.

“We try to keep it interesting. We want the kids to feel like it’s not just an extension of the school day, but a ‘yes, afterschool, woo!’” she said. “They’re going to get their homework done, which is a huge stress relief, and they also get to socialize and do all sorts of activities.”

In the second hour of the program, students typically shift toward the fun, enrichment-based activities. Some days, Bonnet said community partners come in—such as STEM Alliance, Backyard Sports and the Rye Nature Center—while other lowkey times involve social-emotional learning games that foster creativity or simply outdoor play.

They strive to foster excitement among students, which Bonnet emphasized is important because ultimately, a good afterschool program should also fight truancy—students are more likely to want to go to school if they know they get to have fun at afterschool.

And Jean-Baptiste feels their model works.

In her three years of work at the Carver Center, she’s found students who enroll in the afterschool program tend to, if they can, come back year after year.

“I’m happy I get to be in all the schools and know all the kids. It’s funny, I visited Park Avenue School at the beginning of this school year, where I spent a few months straight last year, and these kids came up to me saying ‘where have you been, we missed you!’” she recalled. “That makes you feel good.

“I’m just thrilled we were able to get grants and give families access to this—a quality program where they can be assured their kids are in a safe space.”

Comments:

You must login to comment.